Originally published June 9th, 2020 in German here, translated with http://www.DeepL.com/Translator (free version)

This background article explains where the money for governments in the current crisis comes from and why, contrary to general expectations, the EU will probably not play a major role in this crisis.

The Western states decided relatively late to largely shut down public life in response to the spread of Covid-19 (coronavirus). For they knew from the outset that the near-quarantine would have far-reaching economic consequences. Since the health and economic future is completely uncertain and, for example, pubs and hotels are or were closed, the citizens hardly spend any money. Companies are foregoing investments, and entire industries are lying idle: Lufthansa had to cancel almost all flights, VW had to stop production in Wolfsburg. The workers are therefore unemployed, which makes the applications for short-time work benefits skyrocket. More people are already unemployed than during the Great Financial Crisis of 2008/09. The economy would collapse if the state did not intervene.

But how does the state get its money – and what money? Should national governments spend more? Or should the EU spend more money, and if so, how? The questions mix up monetary policy issues with political questions about the future of the eurozone and the European Union. In this text I will try to separate the two dimensions. To put it bluntly, the crisis will cause economic damage in the form of lost production combined with unemployment. This damage is real economic damage. Less goods and services will be produced and therefore consumed. Nevertheless, we are constantly hearing about the “financial costs” of the crisis. This view of things is fundamentally wrong. Costs are a business concept. They evaluate the consumption of production factors in production. But if less is produced, then there are no “costs”.

The “costs of the crisis” are, as I said, the loss of production and this cannot be “financed”. The demands to distribute the costs of the corona crisis fairly are therefore based on a misunderstanding. The same applies to the financing of the costs of the crisis. Here monetary concepts are confused with real concepts. If, for example, less taxes are paid as a result of the slump in production, then government deficits and thus government debt will increase. Nothing more will happen; the economy will also be able to live with higher deficits and higher national debt.

If necessary, we will have to override a few rules (e.g. debt brake or Stability and Growth Pact) and make a few new rules permanent (e.g. the ECB’s Pandemic Emergency Purchase Programme). However, it is by no means necessary to reduce public debt again in the wake of the Corona crisis. On the contrary: an increase in taxes for the broad masses would certainly drag the economy down even further. What is needed, then, are economic stimulus packages to rebuild the economy. It makes sense to focus policy on the issues of climate change, inequality, the welfare state and common goods and not, as in the wake of the last financial crisis, to promote socially undesirable products with a scrappage bonus.

There are two possible answers to the question at which political level the European economy will be stimulated again by increasing spending. On the one hand, nation states can increase their spending to help their citizens. The alternative is to increase spending at EU level. However, it should be noted that the EU budget is usually financed by remittances from the member states. Increasing the EU budget through higher allocations from the member states therefore does not seem to make much sense – why not simply increase government spending at national level instead of sending the money via Brussels?

An increase in EU spending therefore only makes sense if the money does not come from the member states. On the other hand, it is questionable whether the EU is even in demand. The EU’s principle of subsidiarity states that the level of regulatory competence should always be as low as possible and as high as necessary. So why should the EU spend money when the nation states can do just as well? This point has not been recognised in the political debate because, as explained above, there is a misunderstanding of the economic problem, after the costs of the crisis have to be “financed”.

However, there are political efforts to develop the EU into a United States of Europe. This would include a European ministry of finance (Euro Treasury), which would issue Eurobonds. The ECB would be able to buy these without limit, similar to national government bonds with the PEPP, and would thus turn the Eurobonds into permanently risk-free bonds. This would give Brussels the possibility to issue unlimited money, which would not be possible at national level (provided the PEPP is scrapped). At this point we would have the “crowning glory” of the EU as a result, the transition from a supranational authority dependent on allocations from member states to a real government with its own source of money (Eurobonds and ECB). Such a “coronation” in the crisis without a public discussion of the question whether such a construct of the United States of Europe is even desired by the population would confront us with problems of democratic theory. Our Basic Law, for example, is “eternal”. To what extent can Germany be a democratic and social country (GG §20) if its government spending is then de facto limited by the Maastricht rules and, in crises, the spending of the European Commission (then government) continues to rise while the spending of the German government continues to fall? This would be accompanied by a loss of competence of the nation states. This should be discussed publicly.

The current crisis presents us with the challenge of protecting our people from the Covid 19 virus while at the same time preventing the economy from collapsing. At the same time, politics is not at rest when it comes to climate change, Europe and other areas. In this article I would like to explain where the money for governments comes from and why, contrary to general expectations, the EU is unlikely to play a major role in this crisis.

Short-time working allowance instead of black zero

Up to now, Germany has repeatedly stressed the ban on state financing by the European Central Bank (ECB) and the 3% deficit limit for state budgets. Since Wolfgang Schäuble, the black zero has ruled in the Grand Coalition’s Berlin. Instead of standing for dilapidated infrastructure, lack of state innovation and investment, it should stand for sound budgetary policy. This is why citizens expected little from the economic policy of the German government and the German-dominated European Commission when the coronavirus crisis hit us. However, they are now providing comprehensive proposals for remedying the crisis of the century caused by health policy.

In this country, the short-time working allowance is a traditional crisis-supporting instrument. It is intended to help maintain existing work structures during the crisis so that they can be seamlessly reintroduced later. With the “0” short-time working allowance, the public sector provides a set of instruments that can be used to continue to pay wages (de facto unemployment benefit) under the conditions of merely suspended employment contracts. Anyone who loses his or her job for a few months thus retains his or her income.

The Federal Government expanded this set of instruments at the beginning of March. On 19 March it decided on additional grant and credit aid for small businesses totalling €40 billion.[1] For large companies, “unlimited” (quote from Finance Minister Scholz) credit funds are available through the Kreditanstalt für Wiederaufbau (KfW).[2] The Chancellor’s sentence applies that money should first be spent. Afterwards, one will see what has become of the black zero.[3] Until recently, she vehemently rejected investments in the ailing infrastructure even with negative interest rates for German government bonds.

Commission and ECB have learned

EU Commission President Ursula von der Leyen announced the suspension of the Stability and Growth Pact with its rigid 3 percent rule for new debt, paving the way for her former boss’ spending plans. According to the Commission President, her move means that national governments can pump “as much liquidity as necessary” into the economy. Only the new ECB boss Christine Lagarde initially put the brakes on, as she initially tried to distance herself from Mario Draghi and his “Whatever it takes”, which is not uncontroversial in Germany. The ECB is not responsible for the different interest spreads (i.e. the difference between the respective interest rates in comparison to Germany) on newly issued government bonds of the euro countries.

As a result, investors expected Italy to leave the euro. Italian interest rate premiums shot up and the euro crisis returned. Italy threatened to become the new Greece. The ECB immediately denied that Lagarde’s statements had been misinterpreted. The ECB announced that it would launch a €750 billion bond purchase programme in the tradition of Lagarde. On the basis of this Pandemic Emergency Purchase Programme (PEPP), the ECB buys government bonds from investors at market price until the money is used up. In doing so, it simply increases the selling banks’ balances with the ECB. This money is newly created, it is not tax money [4].

The so-called “issuer limit” is now also being reconsidered. This states that the ECB may not buy more than 33% of a country’s bonds. This detail was originally intended to allay fears that the ECB was carrying out quasi indirect monetary public financing. The ECB is now speculating that it would also abolish this limit: “To the extent that some self-imposed limits might hamper action that the ECB is required to take in order to fulfil its mandate, the Governing Council will consider revising them to the extent necessary to make its action proportionate to the risks that we face. “[6] With such a reform the ECB would send an important signal, because it could guarantee the solvency of all governments in the Eurozone.

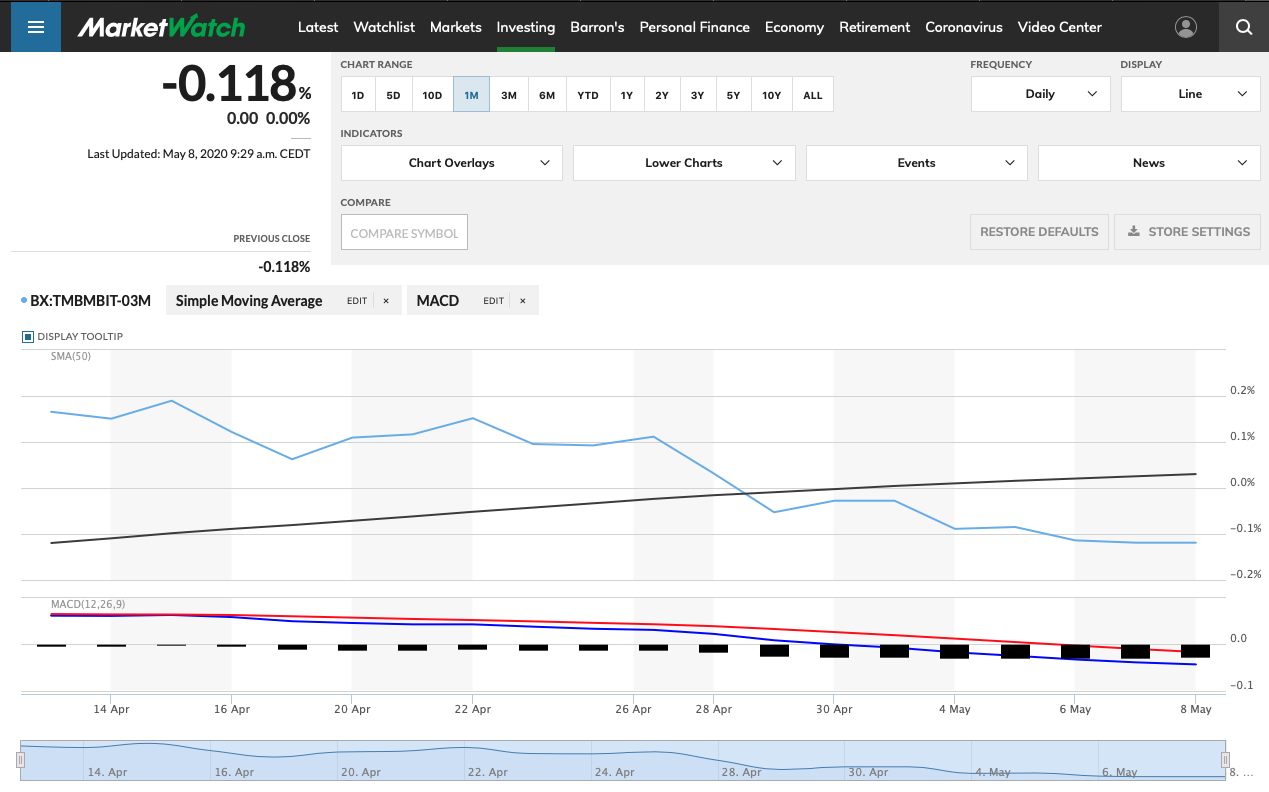

On 24th April Italy decided to increase government spending by 55 billion euros. [8] The interest rate on Italian government bonds with a term of 10 years fell from 1.99% to 1.87% on that day and currently (28th April) stands at 1.75%. [9] This way the Italian government will not run out of money. The Italian government has already rejected money from the European Stability Mechanism (ESM), which was established in the course of the last financial crisis and whose loans were tied to conditions. The ESM is extremely unpopular in Italy and is perceived as an “instrument of fiscal torture”. A European “solution” is therefore neither necessary nor sensible. The national governments can easily get more money by simply spending more. The important question for the long term will be what happens after the crisis. The PEPP can probably not be taken back without raising the interest rates of some euro countries. It would therefore make sense to continue the PEPP permanently. Otherwise we would have diverging interest rates, high where the crisis is, and low where the economy is growing strongly. The ECB is unlikely to want to implement such a recipe for European disaster. The Commission can reinstate the Stability and Growth Pact once the economic recovery is complete – and that applies to the whole of Europe, not just Germany. This is where European policy is needed.

The cost of the crisis – it’s not about money

The German government has recognised that the costs of the corona crisis are not measured in money, but in the loss of real production and possibly even production capacity. These costs can be offset if increased government spending compensates for the loss of expenditure by households and companies. In this way, government spending maintains economic activity. However, if, as is usually claimed, the state had to rely on an increase in tax revenues to increase its expenditure, we might as well forget the matter. With its “counter-financing” through taxes, the state would deprive citizens and companies of precisely the purchasing power that it wants to give them through additional spending.

In the eurozone, too, the central bank ultimately enables the state to make payments. In contrast to the private sector, the euro states do not spend their money with credit balances in private banks, but only use credit balances in the respective central bank money accounts. In doing so, the ECB, together with the banking system, generates money. Either the banks borrow the money from the ECB or the ECB buys government bonds and thus creates it itself. The banks use this money to buy government bonds from governments.

The European Central Bank ensures that this cycle works. It can buy up existing government bonds and thus determine the price of government bonds on the so-called secondary market itself. In doing so, it rejects from the outset any thought of the possible insolvency of a euro state. Investors can always sell to the ECB at current prices. This reduces the risk of default to practically zero. As long as the ECB spends a lot of money on government bonds, this enables the euro states in principle to “pump as much money into the economy” as necessary. [10] A corona crisis does not require it – political will is enough.

The cycle of money

The ECB pumps money into the economy through two channels. First, it buys financial assets such as government bonds, thereby providing liquidity to the banks. If the banks hold a lot of money at the ECB, they can get a lot of cash for it. This prevents a potential bank run. Banks can also transfer money more easily to other banks, which increases confidence within the banking sector. On the other hand, the ECB makes it clear to national governments that they do not have to worry about going bust and can therefore spend more money. Only spending on goods and services directly generates demand, income and production.

The spending policy position in “German-speaking” Europe would be turned upside down. Here it is usually argued that financial markets control the interest rate premiums for government bonds, because otherwise the danger of inflation would get out of control. Governments would have to be prevented from promising good things to the supposedly underage people by means of additional spending. This additional expenditure would lead to inflation via higher money supply growth. That is why the financial markets watch over governments that are themselves democratically legitimised. This is a unique experiment. However, it did not work at all during the great financial crisis. First, the markets overslept the case of Greece. They reduced the ratings of government bonds far too late. As a result, falling prices of government bonds in the crisis countries caused both high interest rates and holes in bank balance sheets. Both exacerbated the crises there before austerity policy forced the states to make further cuts in government spending.

As a result of the coronavirus crisis, the German state is probably spending more money (as of March 23, 156 billion euros are earmarked for this purpose), but at the same time it is generating less tax revenue. Political decisions lead to higher government spending. The German government gets money by deciding on expenditures. That is all, the rest is done by the Federal Ministry of Finance, the German Finance Agency and the bank of the state: the Deutsche Bundesbank. In post-war history, there has never been a case where a German government wanted to spend money and “no money was there”.

Why the state can create money…

The state is the creator of money. Its central bank manages the system of accounts of the banks. The federal government and other state agencies also have an account there. The whole thing looks like an Excel spreadsheet on which only the Deutsche Bundesbank is allowed to make entries according to its own rules. When the German Federal Government pays, the Deutsche Bundesbank increases the account balance of the bank it receives. For example, if the German government pays €1,000, the Bundesbank increases the account of Bank X by €1,000 via computer. This in turn increases the credit balance of its customer.

Government spending by the central government always creates new money. This money then flows back to them when taxes are paid. Modern money is nothing more than a tax credit. The state merely promises to accept its own money for tax payments in the future. The state cannot spend money that it has previously collected, just as I cannot use letters in this text that I have previously “saved” or otherwise “collected” somewhere. From this it follows that “taxpayer money” comes from the fairy tale world. So we taxpayers did not save the banks or the Greeks in the euro crisis. The source of the billions in payments to banks and governments was the central bank in interaction with politicians.

According to current political rules, the Bundesbank may only carry out transfers from the federal government if its account is “covered”. Both the tax revenues and the proceeds from sales of government bonds, which the Federal Finance Agency in Frankfurt am Main carries out on behalf of the Federal Ministry of Finance, end up in the “central account of the Federal Government”. In practical terms, this means that the government issues additional government bonds whenever its expenditures exceed its tax revenues. The requirement that government spending be “covered” by credit balances in the Federal Government’s account limits the Bundesbank, but does not change the technical process of posting credit balances. If this condition were to be overridden, the Bundesbank could therefore continue to cover the expenditures of the federal government unchanged [11].

… and why this doesn’t cause inflation…

If a government is not technically constrained in its spending, why does rising government spending not normally lead to higher inflation? For example, why don’t the Scandinavian countries with high government spending sink into hyperinflation? Why has Japan, with a national debt of well over 200% of gross domestic product, had a much better employment situation than the eurozone for decades and inflation rates that fluctuate around zero?

The correct answer to this question was given by the British economist John Maynard Keynes in his major work of 1936[12] Production, and thus GDP, depends on the total expenditure of the economy. Demand (expressed in money terms) determines the supply (of goods) and thus production. Employment depends on production. If production is high, employment is high; if production is low, unemployment is high. In a situation of under-utilisation of production capacities, more (government) expenditure leads to a higher supply of goods, as companies react to the additional demand. Under these circumstances, if too much money meets too few goods, the adjustment is not made through price changes (inflation) but through changes in quantity.

Inflation and wage growth

If at some point we all go back to work and the state demands more goods, then companies will increase their production due to the current under-utilisation. As a result, they will either lay off less workers or hire more workers. This will not put great pressure on prices or wages, so no increase in inflation is expected. Inflation does not depend on the money supply (however defined), but on the change in unit labour costs. Bobeica et al (2019) also came to this conclusion in their working paper at the ECB [13].

The logic is the following. Suppose wages grow by 4% in nominal terms and productivity by 2%. Companies will then produce 2% more and workers will spend their money to buy production. At the old prices, the shelves would be empty. So companies will increase prices so that they can sell everything and make higher profits. This would be the case if prices increased by 2%. The difference between the increase in wages and the increase in productivity can also be called the difference in unit labour costs. So as long as the state does not pay higher prices for goods or labour during the crisis, inflation is unlikely to rise.

Full employment and money creation

The state can thus ensure full employment by spending more on production and thus creating more employment[14] This can be seen quite clearly in the case of short-time work benefits. Here the state pays an income for which the recipients do not even work. Why then should the state not create jobs for those who have lost their jobs not because of the coronavirus crisis, but because of a continuing weakness in demand? The fact that there are more job seekers than jobs is not the fault of the unemployed. Furthermore, we cannot save on labour. Those who do not work this year will not be able to take up two full-time jobs next year. So it makes sense for the state to base its spending on the unemployment figures. Only when, as a result of full employment, wages and commodity prices rise will price stability slowly come under threat.

The problem in the eurozone is that some governments may not follow this logic. For example, the Spanish government is apparently planning to cut state wages by 2%[15] The money saved from these salary cuts is to be used for unemployment benefits, because the government expects higher unemployment in the near future. Here, a government accepts an increase in unemployment and refuses to support those affected. Instead of spending more money, government employees and unemployed people are played off against each other. Such economic policy measures are due to the euro and the prevailing ideology of the Swabian housewife. So the question arises in the euro zone whether we will see a further increase in inequality in the economic development of countries after the crisis. Italy, Spain and Greece would fall further behind without increased government spending, unemployment would rise significantly and social tensions would increase.

Since the Great Financial Crisis, the Eurozone has had significantly higher unemployment than the EU as a whole, than the US, the UK or Japan. This is undoubtedly due to the low level of government spending before, during and after the Great Financial Crisis. The EU has already recognised this and proposed a European Treasury in the so-called Report of the Five Presidents[16] By issuing Eurobonds it could use fresh money via the ECB to tackle the problems of Europeans. Meanwhile, the EU Commission President confirmed that Brussels would also look into “corona bonds” proposed by Italian Prime Minister Giuseppe Conte. In this case, euro countries would be jointly liable so that the interest rates of the bonds would be lower than those of crisis countries.

Government bonds will be repaid, government debt will not

A higher national debt is often rejected with two arguments. Both are based on equating the state with a Swabian housewife. The national debt, it is said, must be repaid at some point and therefore the state must also align its expenditures with revenues in the long term. In addition, government debt would burden future generations. Both arguments are wrong, however.

The national debt is calculated as the sum of the annual budget deficits of the state. A budget deficit arises when the state pays more money to the private sector than it withdraws from it through taxes. At the same time, the private sector generates a surplus of financial assets. If the government wants to reduce public debt, it must therefore reduce the surpluses of the private sector. It can only achieve this if it continually collects more tax revenue than it spends. Contrary to conventional interpretations, it is precisely the reduction of public debt that is a burden on citizens – and not the budget deficits, which add up to “public debt” and private financial assets. Depending on the distribution, of course, some are burdened more and others less – those who have nothing (much) can have nothing (much) or at least not much (not little) taken away from them. However, a reduction in public debt through higher tax payments means that not a single citizen has more money at his or her disposal.

When citizens or institutional investors buy government bonds, they simply exchange money for fixed-interest securities. When these government bonds mature, the central bank ensures that the government can pay back the money. The fact that the central bank must assume this role is a lesson from the euro crisis. The debt cut in Greece and the austerity policy were big mistakes that must not be repeated. The country has still not recovered from them. So the ECB has to ensure the solvency of the euro countries by buying government bonds worth hundreds of billions of euros, thereby signaling to investors that in the event of a crisis the ECB will give them their money back and that government bonds are therefore risk-free.

Government debt = outstanding tax credits

The “public debt” is therefore nothing more than the sum of tax credits owned by the private sector. They are a consequence of the public deficits of today and yesterday. In this context, high national debt means high financial assets – which does not sound so unattractive for future generations, especially at zero interest rates. [17] In Japan, national debt amounts to more than 200% of GDP. This ensures low unemployment and low inflation rates. The currency is strong, Japanese exports are in demand and the interest rate on government bonds is zero – what is the problem? Anyone who seriously wants to reduce government debt in Germany to zero has to explain who is going to pay the one-off special taxes totalling just under €2,000bn. The lower half of the German population has almost no assets.

Nonetheless, some are already trying to convert the supposed “monetary costs” of coping with the coronavirus crisis into political “reforms” that will further push back the welfare state and impose additional tax burdens on the working population. This neo-liberal policy dresses itself as usual in the narrative of the Swabian housewife. According to a draft law, from 2023 onwards, five billion euros in additional federal revenues are to be generated annually in order to reduce the additional debt that is now arising.[18] We can be curious to see what cuts in state spending and what tax increases there will be in order to carry out the reduction in private assets, which is probably counterproductive from an economic policy point of view, in favour of a reduction in state “debt”. Certainly “we” will have to tighten our belts, with the result that corporate profits will continue to flow.

What can we learn from the coronavirus crisis?

The question “How do we pay for this? “has just died. The money is unlimited, resources are limited. This insight will trigger the development of a new economy based on Modern Monetary Theory (MMT)[19] Now it’s just a question of what resources we use our money to solve our current problems and how we use them to develop future resources for future problems.

If we want to fight climate change with the Green New Deal for Europe,[20] eliminate unemployment in the eurozone by guaranteeing jobs,[21] raise taxes to protect democracy from the power of the super-rich,[22] or whatever problems we want to address – the question of state funding has been overcome. How do we pay for it? With our money. How do we do that? We access our resources and use them in a way that enhances the common good. It is time to gear the political system to our problems instead of arbitrary figures like the state surplus divided by the gross domestic product.

The Corona crisis is thus the beginning of an unideological understanding of the monetary system that, for the moment, is giving back budgetary sovereignty to the eurozone countries. With the additional expenditure that this will allow, active economic policy in the euro zone is once again possible. The exciting question is with what justification this wheel should be turned back again in the future and further in the direction of austerity – and whether this will succeed.

On the other hand, some political forces are trying to expand the EU in this crisis in the direction of a “United States of Europe”. Macron and Merkel have agreed by telephone that the EU should borrow 750 billion € from the capital markets. This is surprising, as the ECB can create money free of charge and without limits. The ruling of the Federal Constitutional Court on the ECB’s purchase of the bonds has also placed the entire European Union under reservation. At the same time, there are increasing voices on the periphery calling for an end to the “Euro experiment”. Spain, Italy and Greece are facing economic crises that will be harder than those that followed the major financial crisis of 2008/09, although Italy has not reached the GDP of 2007 again and Greece is even miles away. We are facing an epochal turn of an era. Understanding the monetary system is fundamental to being able to understand and classify the changes.

Comments:

[1] http://www.bmwi.de/Redaktion/DE/Pressemitteilungen/2020/20200323-50-millarden-euro-soforthilfen-fuer-kleine-unternehmen-auf-den-weg-gebracht.html

[2] http://www.tagesschau.de/wirtschaft/coronakrise-wirtschaft-101.html

[3] http://www.deutschlandfunk.de/folgen-der-corona-krise-wirtschaftsforscher-raten-jetzt.769.de.html?dram:article_id=472295

[4] The then head of the US Federal Reserve, Ben Bernanke, confirmed this in an interview with the programme “60 Minutes”. See twitter.com/StephanieKelton/status/1238199214057959424

[5] The Bank of England is openly considering buying government bonds directly from the British Treasury. This would probably be “monetary public financing”. Cf. ftalphaville.ft.com/2020/03/20/1584724186000/The-Bank-of-England-remembers-its-wartime-roots

[6] http://www.ecb.europa.eu/press/pr/date/2020/html/ecb.pr200318_1~3949d6f266.en.html

[7] This would be an important point of an economic policy response to the coronavirus crisis, which Warren Mosler and the author have recently published. See braveneweurope.com/dirk-ehnts-warren-mosler-a-euro-zone-proposal-for-fighting-the-economic-consequences-of-the-coronavirus-crisis

[8] http://www.nasdaq.com/articles/italy-targets-2020-deficit-at-10.4-of-gdp-debt-at-155.7-draft-government-document-2020-0

[9] http://www.marketwatch.com/investing/bond/tmbmkit-10y?countrycode=bxv

[10] Problems may arise from the deficit limits already mentioned and national debt brakes.

[11] As fewer government bonds would circulate, banks would have to hold more money in the ECB’s deposit facility, which would bear interest at a similarly negative rate as German government bonds.

[12] John Maynard Keynes, The General Theory of Employment, Interest and Money, 1936

[13] http://www.ecb.europa.eu/pub/pdf/scpwps/ecb.wp2235~69b97077ff.en.pdf

[14] Dirk Ehnts and Maurice Höfgen, The Job Guarantee: Full Employment, Price Stability and Social Progress, Society Register 2019, 3(2): 49-65, pressto.amu.edu.pl/index.php/sr/article/view/20605

[15] http://www.larazon.es/economia/20200324/bxfi63qbfrhyteegwecqokfgae.html

[16] ec.europa.eu/commission/five-presidents-report_en

[17] When interest rates are positive, government bonds generate unconditional income for the holders of the bonds. However, they are not the cause of inequality today, because interest rates have been falling since 1980 and in spite of this inequality has risen to record levels during this period.

[18] http://www.spiegel.de/wirtschaft/unternehmen/corona-hilfen-wo-kommen-all-die-milliarden-her-und-hin-a-b02d45bf-ff20-4a31-82f4-5851919d2516

[19] Warren Mosler, 2017, The seven innocent but deadly frauds of economic policy and for the Eurozone; Dirk Ehnts, 2020, Money and Credit: A €-European perspective, 3rd edition

[20] http://www.gndforeurope.com

[21] Esteban Cruz-Hidalgo, Dirk H. Ehnts, Pavlina R. Tcherneva, Completing the Euro: The Euro Treasury and the Job Guarantee, Revista de Economía Crítica 27 (1 ), pp. 100-111, revistaeconomiacritica.org/node/1129

[22] Emmanuel Saez, Gabriel Zucman, The Triumph of Injustice – Taxes and Inequality in the 21st Century, 2020

Das Bundesverfassungsgericht hat

Das Bundesverfassungsgericht hat

Recent Comments